"The guilt we grew into remained abstract."

“You’ll see ruins. You’ll see flowers.”

“You’ll see ruins. You’ll see flowers. You’ll see some mighty pretty scenery. DON’T LET IT FOOL YOU. You are in the enemy country.” An excerpt from the training film “Your job in Germany”, the original manuscript is written by the children's book author Dr. Seuss and mentioned on one of the first pages in “Belonging”. It was meant to warn soldiers about the Germans and call on them to be vigilant. “The German people are not our friends. They cannot come back into the civilized fold just by sticking out their hand and saying ‘sorry’. Sorry? Not sorry they caused the war; they’re only sorry they lost it. That is the hand that heiled Hitler (...).”

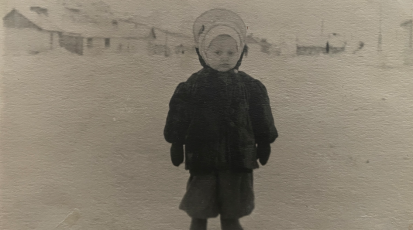

In “Belonging”, Nora Krug tells the stories of her grandparents, her uncle, her aunt – stories that took place during Germany's darkest period. Krug collects snippets of documents, letters and scours archives in Karlsruhe. An attempt to fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle that have been hidden, eaten up. She shows us the context of the horror, the routines of everyday life. But what led Nora Krug to create her Graphic Novel? Was it a feeling of shame resulting from her family's past? Was it guilt she was trying to get rid off through putting those past stories on display? Or rather a feeling of responsibility?

Shame

shame noun

1: a painful feeling of humiliation or distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behaviour.

2: a regrettable or unfortunate situation or action.

Source: OxfordLanguages

On April 16th 1945, the citizens of Weimar were forced to visit the Buchenwald concentration camp. Corpses – stacked on top of each other. The smell of death, all over the camp, was omnipresent. “We didn't know anything about it” said the citizens, especially the women. They were appalled by the violence, ashamed by the horror inflicted by their own husbands, brothers and fathers. It was not just a crime. It was industrial murder. “They killed their neighbors. There was a conscious recognition. Most of them were part of it. Even though they didn't kill someone with their hands, they closed their eyes”, Michaela Köttig, Professor for Fundamentals of Conversation, Communication, and Conflict Management at Frankfurt explains. Acting like you didn't know anything about it is denying the shame, Köttig adds and continues: “These are acts and sights that are very difficult for the human mind to digest and therefore a lack of shame is a mechanism that comes to protect the mind from things it cannot understand.”

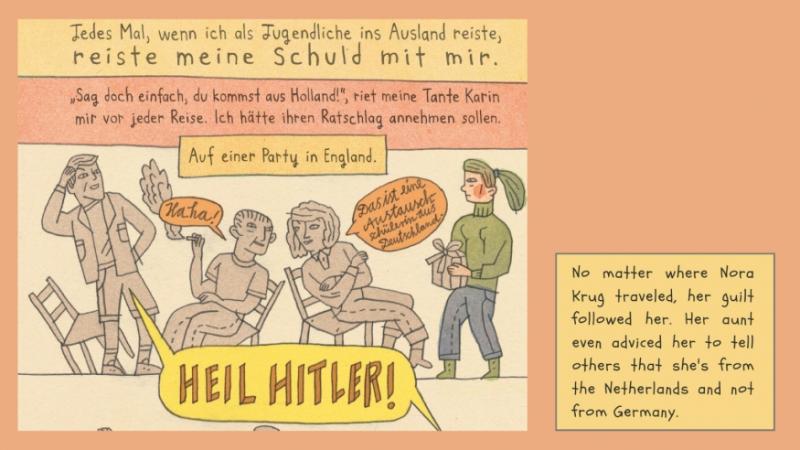

When Nora Krug moved to the US, she “felt more German than ever before”, the illustrator points out. She tried to hide her German accent in order to not be identified as one. Even though the crimes of the Holocaust happened decades ago, there was no feeling of national pride but rather a feeling of shame regarding her home country. And then there's always been the big mystery surrounding the involvement of her family in the Holocaust, a feeling that she couldn’t let go. In “Belonging”, Krug describes her own visit to the Birkenau concentration camp in 1994, almost 50 years after its liberation. Shocked and ashamed of the horrendous actions of her countrymen, she took black and white photos of her classmates to capture the atmosphere of that day. “If we don’t feel a sense of shame looking at these photographs from the camps, I think then something is also wrong with our society. Because it is shameful to see what humans can do to other humans.” When she saw the finished photographs, she thought: Here was the evidence of our collective guilt.

Guilt

guilt noun

1: the fact of having committed a specified or implied offence or crime.

2: a bad feeling caused by knowing or thinking that you have done something bad or wrong.

Source: OxfordLanguages, Brittania Dictionary

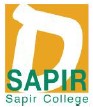

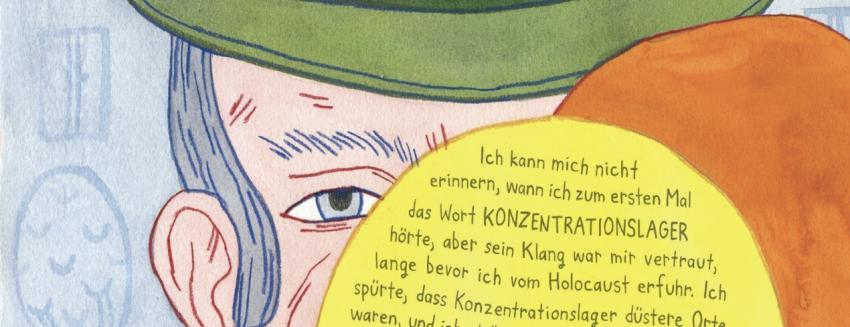

During her time in New York, a city that was one of the most important entry points for refugees under the Nazi regime, being the only German in her environment and getting married to a Jewish man she realized: “It is easier to feel guilty outside of Germany, because you can't hide behind the collective.” The dimensions of the feeling of guilt are displayed throughout the whole book. Krug puts these feelings into words and visualizes them. Many years it was a feeling that was barely talked about at the dinner table. Her years as a teenager were accompanied by a tremendous sense of inherited guilt. “Even though we continuously learn about the Holocaust in school, even though we regularly went on field trips to concentration camps museums, spoke to survivors, analyzed Hitlers speeches word by word – the guilt we grew into remained abstract. And conversations about what had happened in our own families were non-existent”, Nora Krug adds.

Michaela Köttig points out that feeling guilty develops from denying the past: “It's transmitted through the generations who are not talking about the history in any way. The first generation had very vivid and conscious recognitions of the past and what happened. But most of them just covered it. The second generation had a feeling of it, but it was less clear. In this way, the feeling is passed onto the next generation again, but the object of the feeling is not.” In “Belonging”, Krug's feelings are displayed, visible and their source is undeniable: “I’m not saying that Germans should feel guilty. I think guilt can be paralyzing, this is how I grew up, what I experienced. A feeling of paralysis is not helpful for memorializing. Because it stops us from really deeply engaging. So I think the better approach is to feel responsible. But again, I personally don’t have a choice.”

Responsibility

Responsibility noun

1: the state or fact of having a duty to deal with something or of having control over someone.

2: the state or fact of being accountable or to blame for something.

Source: OxfordLanguages

“I think about the political responsibility that I have as an illustrator and storyteller and ask myself what I can do to contribute to dismantling these kinds of cultural stereotypes and perhaps to understand political ideas and cultural perspectives”, Krug says. By embracing her feelings of shame and guilt resulting from the actions of her relatives, knowing that these feelings are real but only echo feelings of a past crime, she was able to work through the stories.

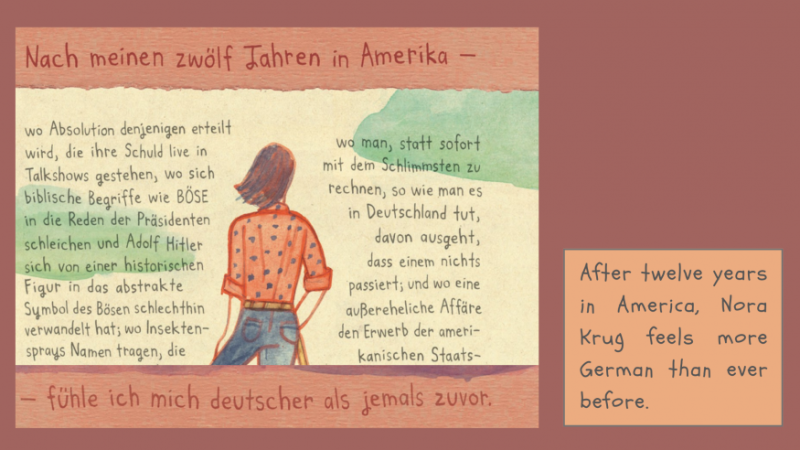

The more time she spent in the US, the greater the urge became to ask her family questions she had never asked before. She traveled to Germany to ask these questions and research her own history. Seeing and reading her grandfather's handwriting in archive documents was an “uncomfortably intimate experience”, it felt like he was “finally speaking” to her. While creating “Belonging”, Krug took responsibility for herself, for her family and those who still suffer under the heavy burden of the past. Readers are taken into a familiar perspective because the German point of view is not in the center of the general commemoration culture. And still, regarding responsibility, it is important to remember all the stories so we can learn from them. “Everyone must pay attention, otherwise we take a risk that history will repeat itself.” Looking at pictures from the concentration camps is an example for a type of responsibility Germans owe to the victims. “If nobody ever photographed the liberated camps, our understanding of the Holocaust would be completely different”, Krug explains.

“Belonging” is critically acclaimed and won many important literature prizes. During readings in other countries, the audience's feedback made Krug realize that no matter how focused the book is on her family and home country, there is a huge universal meaning to it. The Graphic Novel is able to pass on this certain responsibility to anybody to look back at one’s troubled past. Still, Krug received a few negative responses from the extreme right-wing spectrum both in Germany and the US. But those responses might confirm her responsibility of publishing a book like this even more: “I actually feel that I’ve done something right. If I want to be criticized by somebody it’s probably by people from that political spectrum.”

Belonging?

“But they must prove that they have been cured – beyond the shadow of a doubt – before they ever again are allowed to take their place among respectable nations”, another line from “Your Job in Germany”. Even though this film is decades old, it forecasted the feelings a lot of Germans are dealing with until today: Shame, guilt and responsibilty. Books like “Belonging” attempt to visualize these feelings. Author Nora Krug summarizes her personal view on the three feelings: “Shame is just a normal human reaction and I think guilt should eventually be replaced with the term ‘responsibility’.” Dealing with their past is a huge responsibility of Germans. The illustrator thinks that there has been done a lot of institutional work in Germany when it comes to confronting the past. But in her opinion the personal work is still lacking until today. In the end, it’s not a matter of finally overcoming all these feelings but to rather acknowledge and understand them. While dealing with the own past and all the feelings that come with it, one might also be able to develop a better comprehension of personal belonging. Just like one of the essential questions in Nora Krugs book suggest: “How do you know who you are, if you don’t understand where you come from?”