“One could call the Nazis “monsters” in a metaphorical sense, but they were humans – like us.”

Graphic Trauma

For approximately 160.000 Holocaust survivors currently living in Israel, the horrors of the Holocaust are daily present and quite a few suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. They re-experience the trauma they went through in nightmares, avoid talking about their experiences and may react nervously. Graphic novels, comics that not only deal with fiction but also serious non-fictional historical and political issues, can be helpful with traumatic experiences but also reignite them.

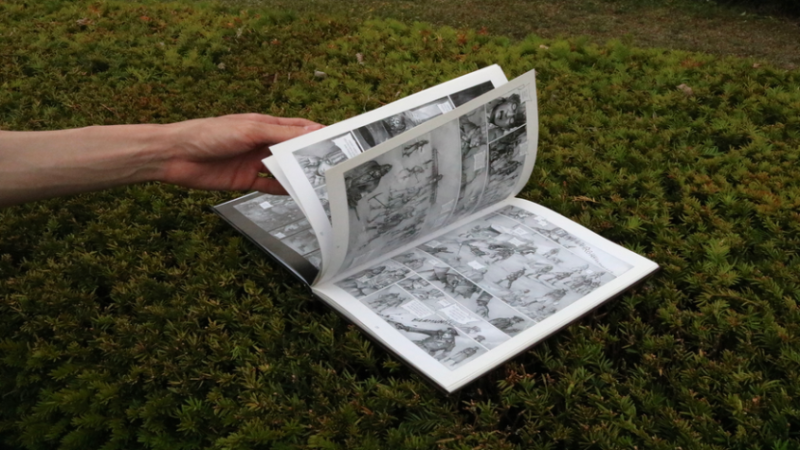

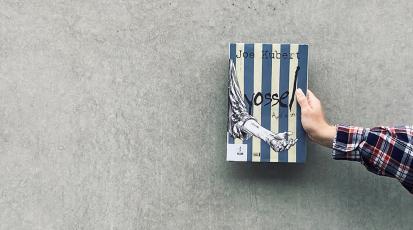

The graphic novel “Auschwitz” by french author Pascal Croci focuses on the traumatic experiences and memories of a husband and wife who survived the Holocaust and lost their daughter during those times. Even though the couple were both in the concentration camp at the same time, they each have different memories and images of their stay there. Now, they find themselves somewhere in Ex-Yugoslavia and are finally talking about their time in Auschwitz. Through each story, there is a difference between the narratives of their traumatic experiences.

Pascal Croci, the creator of this graphic novel, never experienced the Holocaust first hand. Croci's idea and narrative of that time come from stories, photos and images that he has seen and heard. Many of his drawings are inspired by research and interviews with Holoucast survivors. Since he had no personal experience, he had to do interviews and rely on the memories of Holocaust survivors. He picked up their stories and mixed them up to create a new one, so the story he tells about Auschwitz is fictional.

Banality of Evil and Lack of Realism

A striking aspect of this particular graphic novel, besides being fictional, is the way Croci depicts his characters. The humans do not look like humans, but rather like zombies with googly eyes, extremely strong bone structures and sharp fingers. On the back cover it says that “Auschwitz” is the “first realistic graphic novel about the Shoah”. Croci’s goal was to remind the younger generations of their duty to remember the millions of victims of the Nazi-Regime. But do we want to remember them as zombie-like creatures? Shouldn’t we remember them as what they truly were: Humans?

Andreas Langen is a German journalist and photographer who, together with Kai Loges, created a photo exhibition and a book about Auschwitz called “Auschwitz Next Door”. The duo explored the area surrounding the former concentration camp, interviewed the locals and captured it in photographs. Their goal was to document reality, to help one understand the context of the Holocaust and to transmit information and details. Their work is documentary, unlike Croci’s “Auschwitz”.

Langen pointed out that “Auschwitz” is extremely expressive and that one of Croci’s stylistic means was to visually turn the murderers into monstrous, grimacing figures. They are drawn like a combination of alien, zombie and Dracula: a monster. Their faces do not look human, but the Nazis were in fact human beings. “One could call the Nazis “monsters” in a metaphorical sense, but they were humans – like us,” Langen states. He finds Croci’s creative and dramaturgical decisions to be completely wrong. Adolf Eichmann, SS-Obersturmbannführer and one of the major organisers of the Holocaust, did not look like this and neither did the other members of the Schutzstaffel. They were people, they were homo sapiens.

Hannah Arendt, a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor, wrote in her study of the case “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” that Eichmann was not an amoral monster. Still, we do not want to belittle the crimes and the evil that came from the Nazi regime.

Visualising Evil

Croci chose to draw his graphic novel in black-and-white – no colours. In order to find out more about how one sees the Holocaust visually, we created a questionnaire. In our questionnaire, 50 people that live in Europe and North Africa participated. Half were in some way connected to the Holocaust, the other half had no connection to it. Although there were many different national backgrounds (Jewish, German, Polish, Croatian et cetera) as well as age differences (15 until 50 years of age) and differences in generations (second, third and fourth generation), we could see many similarities in their answers. When asked about what colours they associate the Holocaust with, the vast majority chose black, grey and red. Also, when asked what images come to mind when thinking about the Holocaust most said fences, starving people standing in a line and corpses.

In an attempt to better understand the representation and transmission of traumatic images of the Holocuast to newer generations, we met with Dr. Martin Auerbach, National Clinical Director at “AMCHA”, the largest provider of mental health and social support services for Holocaust survivors in Israel. Auerbach is a psychiatrist and psychotherapist and is also specialised in trauma therapy.

When asked about how most of the people who have not experienced the Holocaust first hand associate these colours with the Holocaust, he explained that it has to do with the fact that most of the images of the Holocaust and historical events are black-and-white. At the end, it comes down to the amount of exposure to imagery and colours we absorb. Furthermore, he adds that future generations will actually associate real colours with the Holocaust and other historical events because we add colours to the images nowadays. He argues that the historical photos and images younger generations will be exposed to will be colourful.

Auerbach’s opinion concerning graphic novels is that the story itself can be helpful with traumatic experiences, but when the exposure is overwhelming and when the imagery is very vivid it pushes people away. Overexposure to such images can even trigger trauma as well as cause retraumatization. When it comes to trauma there needs to be very delicate exposure and imagery that is not too horrific. Croci’s graphic novel would fall into the latter category.

Graphic Responsibility

Although a graphic novel is indeed a way to deal with trauma and the Holocaust, one must be careful how to depict it. Croci states to be the first realistic graphic novel about the Shoah but missed the mark. Instead of drawing a realistic depiction of Auschwitz, he created a graphic trauma. You do not get any closer to reality if you distort it into a graphic monstrosity. One does not need to draw monsters to depict the evil of the Nazis – it is enough to get to know the facts.