"We've done a lot of institutional work in coming to terms with our past, but in my opinion we haven't done a lot of personal work."

Beyond NS Family Tales - investigating the past

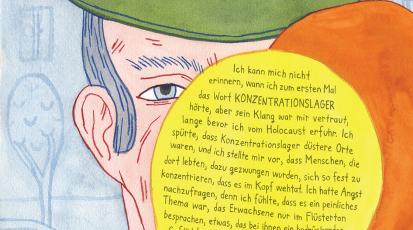

Concentration camps, deportation, the Holocaust – terms many Germans learned in history class. "They have done a lot of institutional work to come to terms with our past," says author Nora Krug in an interview. But for a deeper understanding, she adds, it is much more rewarding to deal with history personally – as she did in her book "Belonging", a graphic-literary family album about how National Socialism affected her family.

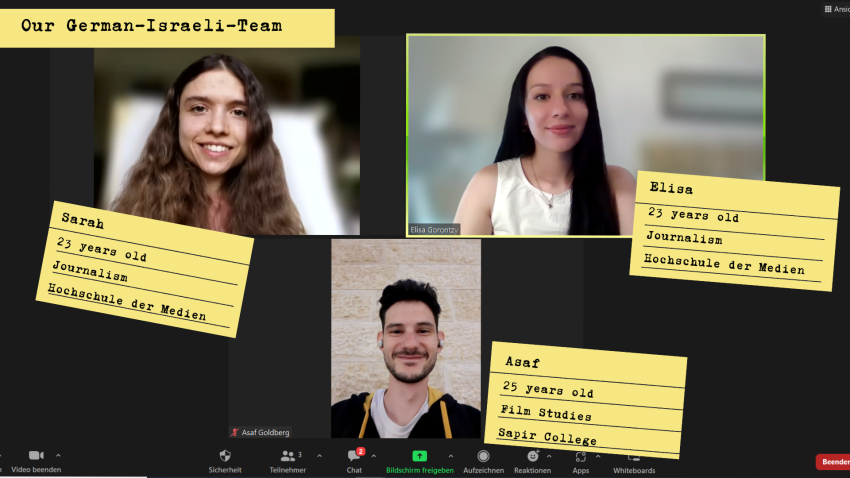

As a German-Israeli team, we were inspired to investigate our own family tree for traces of National Socialism: We are Sarah, Asaf and Elisa, three students. As part of the international project "Holocaust in Graphic Novels", we are embarking on personal research into our family history from three different perspectives – because we believe that personal research leads to a much greater understanding of our past.

Elisa – about the first icebreaker

"Have you ever wondered how much your family was involved during this time?", Sarah asked me, Elisa, as a German team member. Hesitantly, I replied that I had thought about it once, but not more. Why had I never talked about it with my family, or my family with me? I was even a little ashamed to talk in front of Asaf about the fact that we young Germans might have active Nazi ancestors in our family tree. The conversation seemed inhibited at first.

Asaf quickly took the floor and shared anecdotes from Israeli speeches about the Holocaust, saying: The events of that time have become part of everyday discussion, humour, stories and culture, and are not confined to the classroom and history lessons. Talking about it is free and there is no discomfort in talking about what happened, no matter how horrible it was. But his experience is limited to the last few decades of Israeli history. He thinks that the discourse on the Holocaust in the first decades after the establishment of the state was very different.

Asaf asked us to speak just as freely about what we know about our families from that time. This is what interests him, and he thinks that openness is the best way to deal with history – very personal and very close.

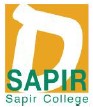

Elisa – about heirlooms as signposts

Elisa wondered how best to approach her family about her grandfather (born in 1929 and died in 1999) and what he thought of National Socialism: "It's not an easy subject, of course, and I didn't dare ask at first," I told Nathalie Jacobsen. The historian works at the NS Documentation Centre in Munich, an institution that focuses on the history of National Socialism, looking at the past and the present. "Try it with an object, start the conversation with an old photo of your grandfather," Nathalie Jacobsen replied. Throughout her career, she has often noticed that older people in particular want to talk about their memories. But they don't dare to start. "That is the job of the younger generations, who can talk to eyewitnesses," says Nathalie Jacobsen.

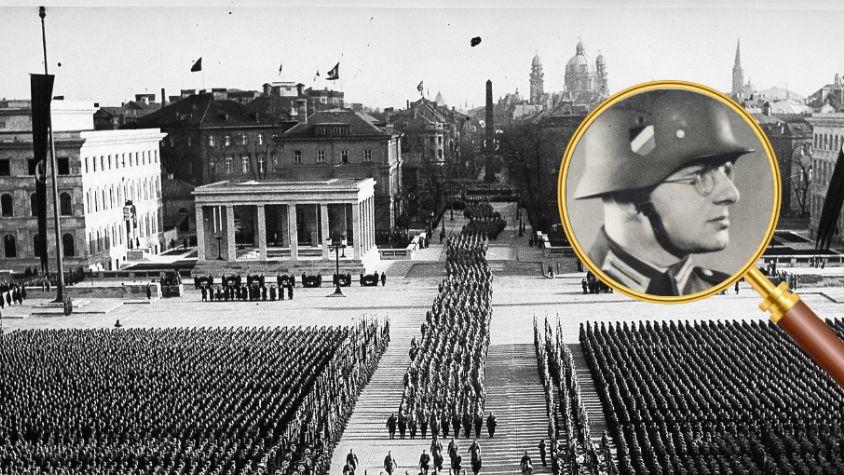

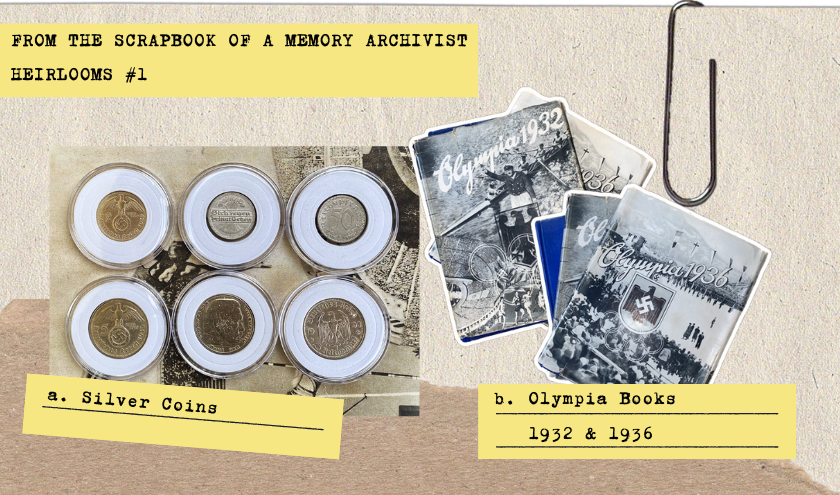

I took Nathalie's advice to use a picture and, after talking to my father, I knew that my grandfather had been in the Nazi youth, poor after the war and very reserved as an adult. He never talked about National Socialism, but he did leave some questionable heirlooms: A few Reichsmarks and two dusty books, Olympia 1932 and Olympia 1936, with Adolf Hitler on the cover and numerous reports on the Berlin Olympics – which we now know were meant to distract from the Nazi atrocities in the concentration camps. Why did my grandfather keep all these things?

Elisa tries to break down all the information about the heirlooms: My father told me that his father had left this collection to his children because he believed they could make money from it, not for ideological reasons. I looked again at the silver coins and discovered the one with the inscription 'Sich regen bringt Segen' from the Weimar Republic of 1919, the first period of parliamentary democracy in German history. So I believed my father's statement that my grandfather had collected all kinds of coins without any ideological interest. Still, I felt a little guilty and ashamed when I showed the heirlooms to Asaf, our Israeli team member.

Asaf – about the significance of heirlooms

When Elisa showed me, Asaf, the heirlooms, I was interested in them. I think there is no reason to feel bad about keeping them. They are important parts of history and worth preserving. Family heirlooms are part of history and part of our connection to our past, and that does not mean that we share their ideological implications. But there has to be a clear distinction between preserving things for their historical value and proudly displaying them as part of one's personal heritage. I find it interesting to compare the significance of family heirlooms in Israel and Germany. Any memento of German military history is frowned upon (for legitimate reasons). In Israel, on the other hand, the cultural memory of war is often treated with admiration and respect. Heirlooms that are kept and displayed are seen as reminders of heroism. In my opinion, anyone who has a problem with German family heirlooms and stories should also look at the role of their grandparents in the wars of Israel's past and study the actions of their own ancestors during these events, which are now considered heroic. It's always problematic to compare another conflict with the Holocaust. But I think the cultural memory that prevails in Israeli culture is perhaps not as heroic as it is taught and talked about. At least for me.

Sarah – beyond family tales

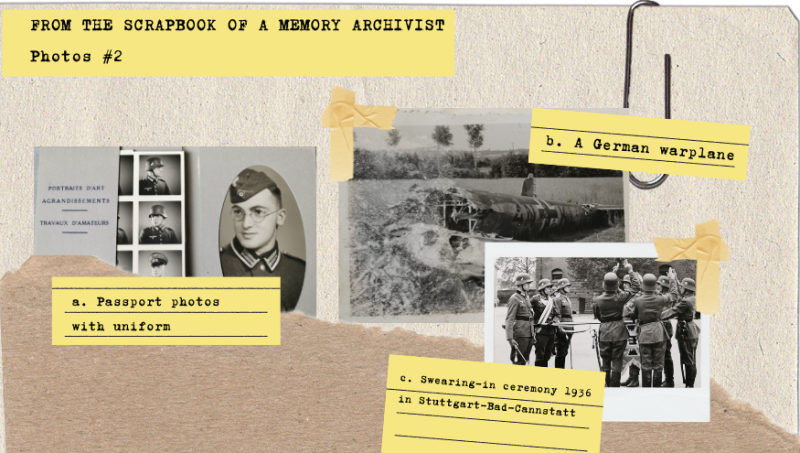

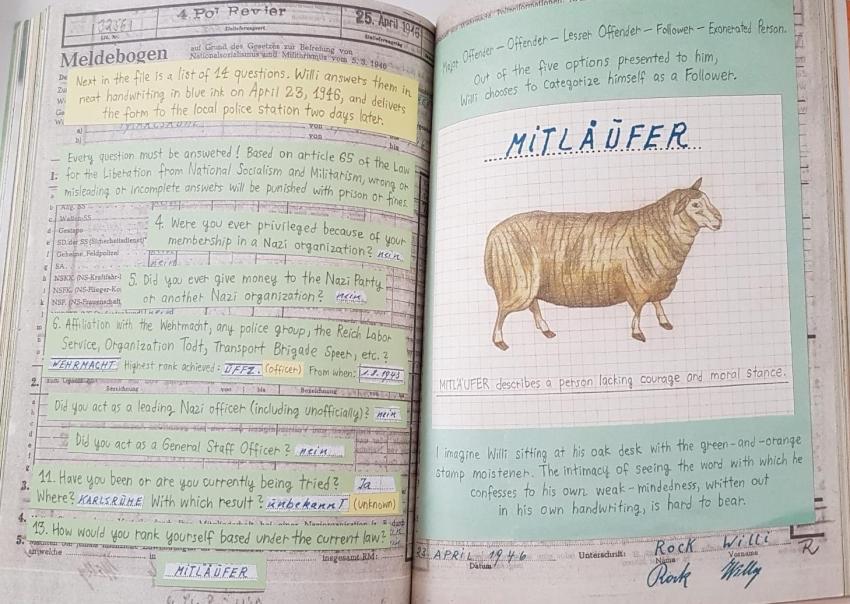

Remains such as photographs and documents are important sources of information. If you want to find out about your family's history and conversations are no longer possible, then written documents are your only recourse. This was Sarah's first thought when she started researching. Her great-grandfather had kept a diary and left a few clues, so there are books and photographs piled up on her desk.

Sarah questioning her great-grandfather Ludwig (born 1914, died 2008): He is said to have worked as a doctor in a military hospital for German soldiers – a profession that raises many doubts in my mind: What did he know about the Nazis? Out of what conviction did he work for them? Was he just a follower or an incriminated person?

Definition of being a Follower:

The so-called "Spruchkammer files" examined the extent to which a person had been active in National Socialism. There were five categories: Main culprit, incriminated, less incriminated, follower and exonerated.

In the western zones, one million citizens were classified as followers by 1950. They submitted to the system, were registered as members of the NSDAP, attended obligatory meetings and paid membership fees. In this way they supported the regime without taking an active part.

Nora Krug struggled with similar questions in her book Belonging, in which her grandfather plays a central role. With each piece of evidence, her feelings towards him alternated between sympathy, shock, understanding and complete incomprehension of his life.

Sarah about her great-grandfather: Ludwig wrote about his experiences in a series of eyewitness books. I also found detailed diary entries from before the war until his death. I read that he had worked as a medic in a military hospital in France because he did not want to fight, which at first relieved me. But I was also depressed that I couldn't find out more! I could not be sure how much he knew about what the Nazis were up to. After the capitulation of Germany in May 1945, he reports that they had to carry the sick and wounded who could not walk themselves to the victory celebration. "During this, all the hatred was unleashed. A small French civilian kept shouting at me: 'Buchenwald, Buchenwald' and made the sign of a cut throat. I did not know what that word meant at the time". He states that he only found out after this experience when asked by an officer. Unfortunately, neither my grandmother nor other relatives ever spoke to him about this time. When I interviewed my grandmother, I found out why:

According to historian Nathalie Jacobsen, it is much easier to deal with family history today because it is not as guilt-ridden as it was after 1945. Grandma's sudden willingness to answer questions was exciting to witness. As we talked, it seemed particularly important to me to ask what my great-grandfather knew about the Holocaust. It's a pity that she can't tell me more than what my great-grandfather had written down. My grandmother and my great-aunt insist that their father knew nothing about the murderous intentions of the Nazis – but is that true? I knew I wouldn't get close enough to the truth if I only interviewed my family. It was only with the help of the French historian Damien de Santes that I was able to put my grandfather's knowledge of the Holocaust into a historical context.

Sarah – putting one and one together

Damien de Santis made it clear to me at the beginning of our interview that the question of what people knew about the deportation is very complex and there are no easy answers. But what I was able to learn about my grandfather through his expertise was of great value to me. He told me that the BBC played an important role in official communication in France, as a large part of the French population, from all walks of life, listened to it during the German occupation. Through its reporting, information about the Jews deported to France was widely disseminated. As my great-grandfather was religious and was in Paris at the time, it is unlikely that he did not know. In France in 1942, everyone, even the official government press, talked about religious protests. "So it's quite impossible for someone in France in 1942 not to have heard about the information circulating through the religious authority.

Even if he hadn't heard about it through public channels, he would have heard about it through rumours. "However, it is difficult to say whether he was aware of the Nazis' murderous intentions, since the French population believed that the deportation was merely a population transfer," Damien de Santis points out. But if my great-grandfather didn't know about the Nazis' murderous intentions at the time, he would have found out in 1945, when the first survivors of the concentration camps returned home. But he didn't tell his children, and he didn't write about it in his diary: The only thing he wrote was that he knew nothing about the concentration camps. The rest he hid in his books and from his family – out of shame? Anyway, it was hard for me to have it confirmed that my grandfather, like most others, simply left the Holocaust out of his writings, even in retrospect. But I was relieved to read that he was not a supporter of the system. Time and again, his statements suggest this: "When the German salute was introduced here after Hitler's assassination, I didn't really like it any more," he wrote.

I could spend many more months researching my grandfather, for example, to find his Spruchkammer file – Previous attempts were unsuccessful – and find out if he was a member of a Nazi party or organisation. But I already feel closer to his story than ever before. It will certainly keep me busy for a while and I may do more archival research.

How to research on NS family history

In the course of our research, we noticed that the role of family members in the Second World War still seems to be a topic that people prefer to keep quiet about. Studies by the Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence in Bielefeld confirm this: According to the "Memo Deutschland" survey on the culture of remembrance, two thirds of those questioned consider it useful to deal with their own family's history during National Socialism. Half of German families have never or only rarely talked about it. We decided to give it a try and undertook the following research on the traces of our family history:

Conclusion – personal work on NS family history

School is and remains the place where one comes into contact with history and learns about the terrible past of the Holocaust. However, one's own family history is usually not discussed, neither in Israel nor in Germany. Contemporary witnesses and relatives are becoming increasingly rare. Yet it is precisely this personal confrontation with the past that is so important: "When you do research on a specific person, it is much easier to understand the history around them than when you do research on the whole population," says historian Damien de Santis. So it's a chance for us to be detectives in our own family's period of National Socialism – for our own better understanding of our history, but also for the generations that will come after us.

Our German-Israeli teamwork

For a semester, we worked intensively together across national borders, learning about each other's cultures and different perspectives on the past and present. As a team, we tried to come to terms with our shared history – for the benefit of German-Israeli relations and future generations. We believe that it will also be valuable in the future to deal with conflicts that may later be history, but that we are experiencing today. Political events – in Europe and in Israel – overshadowed our work throughout the semester. The next generations will need to continue to work across cultures and places in the hope that countries will come together again. Historian Natalie Jacobsen also sees this as an important task, saying: "If we can start a conversation with each other, with an open and understanding mind, then that is a very big step towards a healthy society.”