"I felt like i couldn´t go on this journey with people who might be going there with different intentions."

The Fourth Generation

On the Holocaust Remembrance Day in Israel everything comes to a hold. People, cars and even trains freeze as loud sirens can be heard throughout the whole country. Its a tradition and almost everybody turns silent in a minute of remembrance of the victims lost to the Holocaust.

After the Second World War, it was not only cities that layed in ruins. War and persecution are followed by trauma, which correspondes to the extent of the crimes committed by the Nazi regime. What comes after is a lot of work. Until today, people commemorate the victims in this horrible time. Some mourn their ancestors others try to keep up the remembrance of the crimes, to prevent something like this from ever happening again. It is obvious that the two countries especially involved in this form of commemoration are Israel and Germany. Both countries, four generations after, are still dealing with their past. Ancestors are Holocaust Survivors on the one hand and Nazis on the other. As a journalist Team of one Israeli Student and one German student, we wanted to find out: What changed? How do we commemorate in our own ways? What moves today's Generation from both countries ? And maybe there is even some common ground to find in the different experiences.

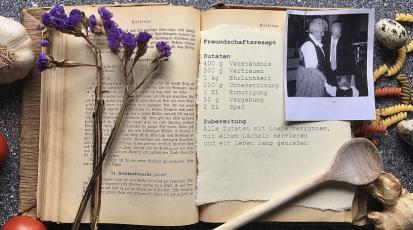

Getting to this point in our binational student project, was started by two special graphic novels, thematizing commemoration and following generations of the Holocaust in a comic like style. The first one is “The Second Generation” by Israeli and Belgian author Michel Kichka, which deals with family dynamics influenced by the Holocaust and follows the relationship of Michel Kichka and his father, who is a survivor of the Holocaust. The Second one is by the Israeli writer Rutu Modan. In her novel "The Property" a grandmother and her granddaughter travel from Israel to Poland, to follow the traces of her grandmothers past before she had to flee during World War II. They both represent the hardships of the second and third generation, address family secrets, and refer to different ways of dealing with those experiences as well as different ways of commemoration.

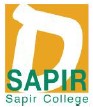

Similar to our Interviewees, both books also express critique to sensationalist ways to commemorate. "The Property" even starts with an airplane full of chaotic students on their way to the camp in warsaw, being silly and loud. Furthermore the classes tour guide casually mentions Treblinka, Majdanek and the gas chambers, commenting on how scary and entertaining they are.

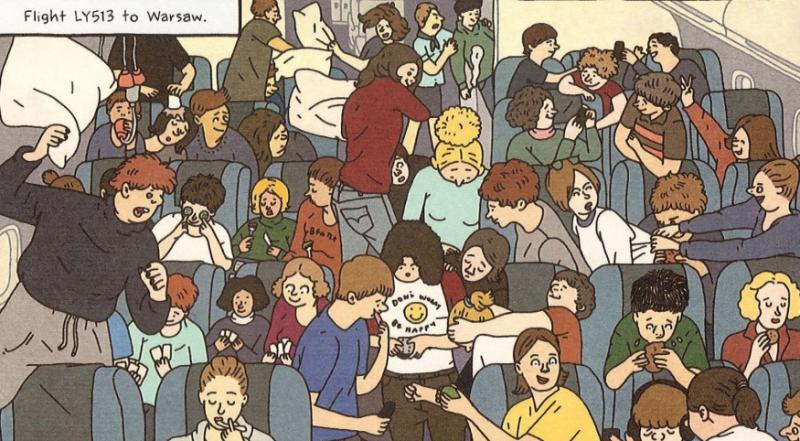

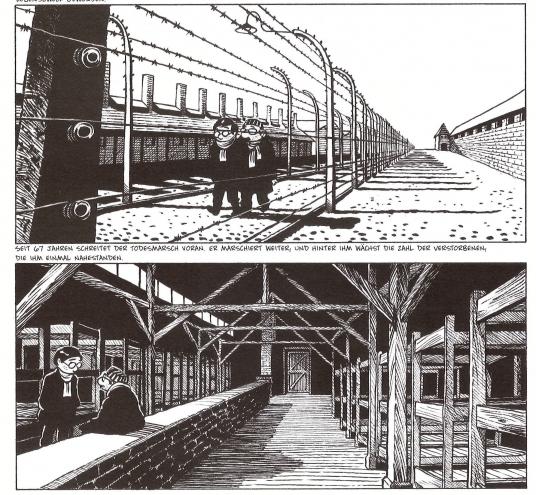

Similar feelings of direct descendants of holocaust survivors are represented in a scene in Kichkas “The second Generation”, describing the first time, Michel Kichka and his father visit a camp together. Kichka explains that he never felt the need to go there as he was young and that he did not want to go with the other Israeli students, proudly holding their flags as a patriotic act. "The Shoa is a matter for all mankind (...) one should go there with humility", is written underneath a picture displaying students with Israeli flags marching through a camp (second slide).

Both Rutu Modan and Michel Kichka compare different ways to remember the Holocaust in different countries. Both seem to suggest a multinational exploration of the past that is open for dialogue. In their novels they pledge to not view commemoration exclusively as a national matter, but as a matter that should be discussed internationally with a strong focus on the present and different realities.