"Instead, the medium is the message. By claiming the Holocaust as a subject fit for comic-book art, Mr. Spiegelman is saying that the children of the survivors have a right to the subject too and have their own unique problems, which are comic as well as tragic."

Of mice and cats

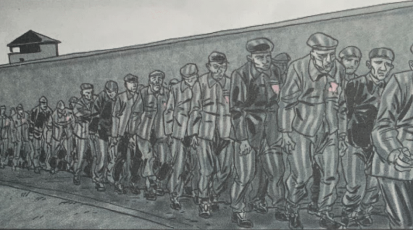

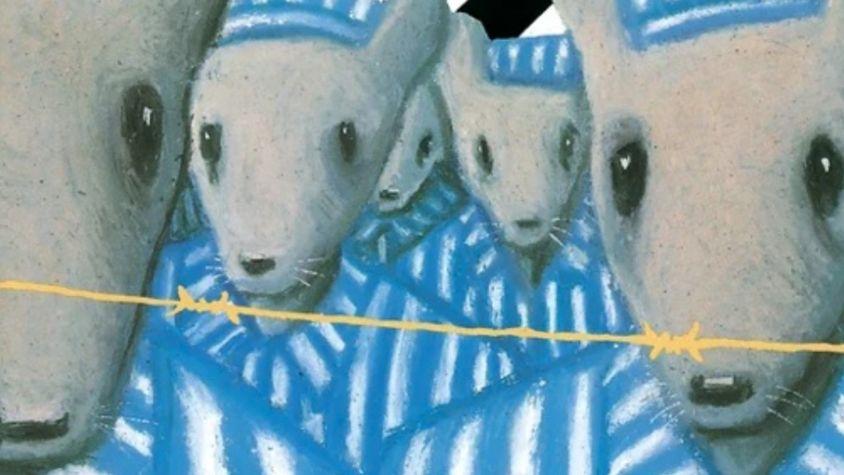

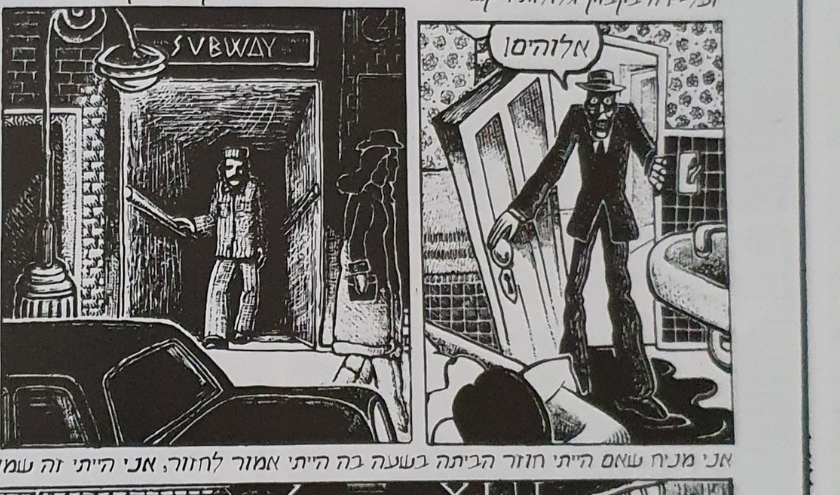

Art Spiegelman drew his graphic novel "Maus" between 1980 and 1981. The different chapters of both volumes were first displayed in Spiegelman's comic magazine "Raw". In 1986, he then published the first chapters as "Maus - A survivor's tale". The graphic novel depicts the life of the Polish Holocaust survivor Vladek Spiegelman, who is the author's father. In "Maus" Spiegelman draws the Jews as mice, the German as cats and the Polish as pigs.

Tennessee removes "Maus" from curriculum

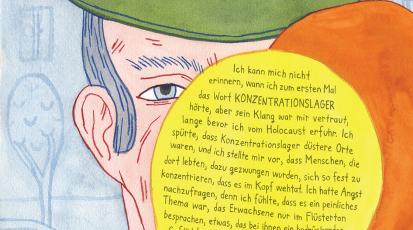

Although "Maus" was published 36 years ago, it still is very popular in the U.S. However, there have been recent news in Tennessee: In January of this year the graphic novel was supposed to be implemented into the curriculum of eighth graders in the city of Athens. But then the school board intervened and decided to remove "Maus" from the curriculum before it was even taught. The main reasons for the removal were one small scene of nudity and the violence of the horrors of the Holocaust shown in the graphic novel.

The case was widely discussed in the media. The CNN even got the author for an interview to talk about the case. However, it seems like the motivation for the removal, which was not actually a ban as many newspapers and media claimed because it is still available at the school library, was not of an antisemitic background. Sophie Kasakove, a former New York Times reporter, who wrote about the case, summarizes her impression of the case in Tennessee:

Becoming the first and only Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel

After it was published as a book in 1986 in the U.S., the New York Times published a review of the book. In it, the journalist Christopher Lehmann-Haupt depicts four things that surprised him: first, the exploration of Spiegelman's relationship to his father; second, the humor in the book although the topic is very heavy and serious; third, portraying his father's story in form of a graphic novel and lastly, how the artist decided to draw the different groups as animals. All of these things were very innovative, but especially choosing the style of comics to convey the terrors of the Holocaust was something no one had done before.

Overall, the book received good critics. It is told to be one of the founding books of the genre graphic novels, which are comic books with more serious and intricate story telling and especially suited for adults. In 1991, a second volume followed with more chapters, especially concentrating on the time Spiegelman's father spent in the concentration camp of Auschwitz. A year later, Spiegelman was not only doing an exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art about the making of the books, but he also won a Pulitzer Prize for it. Until this day, "Maus" is the first and only graphic novel to ever accomplish such a huge recognition and prize.

Germans concerned if graphic novel is morally acceptable

In Germany, the reception of "Maus" was overall very positive. Released in German language in 1989, the graphic novel received critical acclaim. The German newspaper "Süddeutsche Zeitung", for example, described "Maus" as "a haunting picture novel". The newspaper "taz" praised the comic as "a work of the century". "Expressionist picture strip", was what the journal "Spiegel" wrote after the release. At that time, most authors asked themselves the question, "A comic about Auschwitz — is that even allowed?" They came to the conclusion: Yes, it is.

There are only a few criticisms that came up in the early days of "Maus". Among them, for example, the depiction of the Jews as mice. As a German, one is initially taken aback by this depiction and wonders whether it isn't discriminatory. This thought is also shown in a "Spiegel" article from 1989, in which the author asked himself the rhetorical question "Jews as mice?" And then names the following as a grim answer from the author Art Spiegelman:

"Jews as mice? It's the grim and desperate response of a Jewish cartoonist to Hitler's quote 'It is only right and proper to rid the world of an inferior race that breeds like vermin.' "

In 1995, a poster of "Maus" was confiscated in Germany for alleged Nazi propaganda. The poster, produced in 1990 for the Erlangen Comic Salon, showed the same motive as the cover of the comic. The problem here was the swastika in the background. In Germany, the use and display of the swastika as an anti-constitutional symbol is a punishable offense if it is not done for the purpose of clarification or to ward off unconstitutional efforts. Showing swastikas is actually only allowed in art. But seeing a swastika in Germany is always unusual, and the population mostly feels uncomfortable seeing it. This is possibly the explanation for this individual case of confiscation.

Today, Art Spiegelman's "Maus" is highly regarded in Germany. Even the conservative German daily newspaper "Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung" (FAZ) titled in 2021 "This comic belongs on the curriculum".

Despite republication, "Maus" has no success in Israel

In Israel, "Maus" received critical acclaim. The Israeli newspaper "Haaretz" praised the graphic novel " 'Maus' is a wonderful example - probably the most famous example - of brilliant use in comics, a genre that has its (Jewish) roots in popular and entertaining literature, but has long established its new status as high, artistic and critical literature. The very bold choice of Spiegelman to tell the story of his father Wladek, an Auschwitz survivor, through comics, surely gives him uniqueness and sets him apart from thousands of other survivor stories; The use of animals as representatives of different nationalities."

Although it had good reviews, it didn't become as popular as it was expected to be by the Israeli publisher of "Maus", Meron Eren.

Meron Eren is not a publisher, nor makes a living of it - he publishes books as a hobby in his publishing house "Mineged". He was first introduced to "Maus"' around the 90s in Italy. "When I came back to Israel, I just could not believe I did not know this thing and did not believe it wasn't published in Hebrew'", he continues "I found out that the first part of 'Maus' was already published by a different publishing house, and they published a limited edition. In retrospect, I found out that Art Spiegelman did not give them permission to publish the second part of 'Maus'. Then the first part ran out of stock, it was impossible to get it."

"In Israel, the graphic novel 'Maus' got good reviews, but it didn't become as popular as it was expected to be by the Israeli publisher of 'Maus'. "

The process of getting the rights to republish "Maus" in Hebrew again wasn't easy, Eren had to use his publisher's friend's help and had to convince Art Spiegelman himself that this time he''l do a better job than the people who first published the graphic novel. The production and the translation process weren't easy as well, he looked for the best translators and sent the translation to Spiegelman himself, who again gave it to experts for Hebrew translation at U.S. universities.

The first Hebrew edition of "Maus", which had been published in 1990, had not been received well. A poor translation and the sensitive topic of the Holocaust were two of the reasons for the mixed reviews and the refusal of Spiegelman to give the rights to publish the second part. One would think that the changes in translation, the popularity of "Maus" around the world and the fact that the Holocaust became a major part of the discourse on Jewish identity in the past years would be enough to bring "Maus" the popularity among the Israeli crowd, but apparently it didn't work out like that.

When Eren finally met Art Spiegelman, Spiegelman told him that in Israel people like to own the Holocaust for the benefit of Israel, and it won't work here. "And, he was right", says Eren, "comparing 'Maus' sales figures in South Korea to the ones in Israel, the book sold far less. I do try to have a copy of 'Maus' in each bookshop and each comic book store."

When the book was republished in Israel in 2010, Eren took every action to bring "Maus" into the Israelis' recognition. He turned to Yad Vashem, and he turned to Beit Hatfutsot (the diaspora house), and Beit Hatfutsot did not agree to put it because there is a swastika sign on the book's cover.

But what Meron Eren wanted the most, is for "Maus" to become part of the Holocaust studies in high schools. While around the world, in countries like Australia and South Korea "Maus" is considered a compulsory book in schools, in Israel most of the students and the teachers don't even know it. "When my kids were in high school, I gave their history teacher a copy, and she did not know the book. She was so happy; she used the book as a study material before they went to Poland." He continues, "for me, this is absurd."

He tried to convince the Ministry of Education to put the graphic novel in the curriculum, and said he's willing to gift the book to every public school library. "I didn't even ask for money; I just wanted each school to have one copy." Still, Eren says that every person who has read "Maus" applauded him for bringing it to Israel. "But honestly" says Eren, "all the applause goes to Spiegelman, not me."

The handling of the graphic novels in the U.S., Germany and Israel shows one thing: no matter which culture or context - the comic "Maus" creates from time to time a social discussion about the Holocaust. In this way, Spiegelman makes a lasting contribution to ensuring that this is not forgotten.