"Every type of school should support pupils in deciding which training or course of study they can use to fulfill their career aspirations."

Classroom Chronicles: How Social Background Impacts Academic Sucess

What exactly is a working-class child?

"From working-class kid to CEO", "my rise as a first-time academic" and "today's doctor used to be a working-class kid" are some headlines you may have seen in the media recently. But what exactly is a working-class child?

Working-class children can be used as a synonym for non-academic children. Non-academic children are people whose parents have not studied. This also includes children of the self-employed, employees, and those not in gainful employment. If there is no university experience in the family, the term "first generation student" is often used, especially in the Anglo-American world. The term "academic children" refers to people who have at least one parent who has studied.

Sources: Hochschulbildungsreport; ArbeiterKind.de

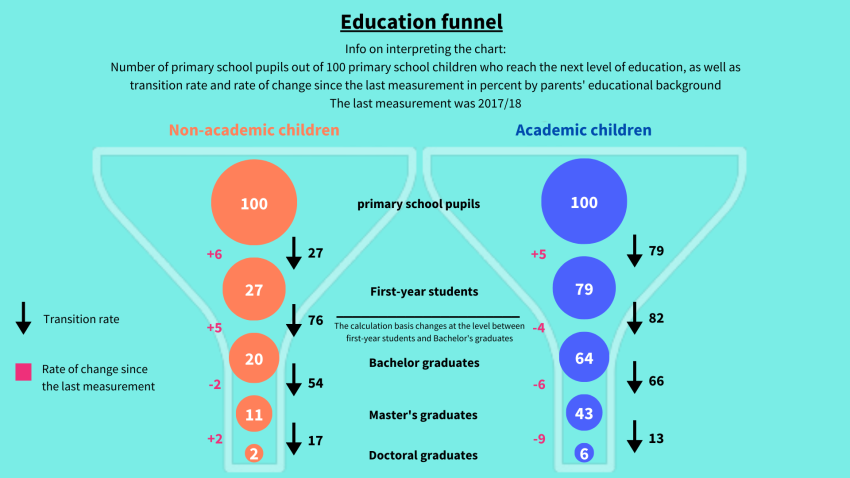

According to the final report 2022 of the Education Report Germany, their education funnel shows that the social background of children still greatly influences their educational success. Only 27% of elementary school (Grundschule) pupils from a non-academic household go on to study. In contrast, this figure is 79% for the children of academics. The proportion of children from non-academic households among all pupils is only 47% - at schools, however, it is 72%. If you take a closer look at the graph, you can see how the situation worsens for working-class children. While a total of 6 out of 43 Master's graduates from academic households complete their doctorate, only 2 out of 11 Master's graduates from working-class families complete their doctorate.

Career orientation and preparation

I myself am a working-class child and the first in my whole family to go to university. My Bachelor's degree is within my grasp, and I can now look back with pride on my academic career to date. But that wasn't always the case. While many of my fellow students went to grammar school (Gymnasium) after elementary school and completed their higher school certificate (Abitur) in the traditional way after year 12, my educational path began with secondary school (Realschule). In contrast to grammar school, at secondary school I was prepared for my later professional life mainly through various work placements during school, most of which related to apprenticeships. As a teenager, I found this incredibly helpful as I was able to gain my first experience of working life. Despite this, I was always given the feeling that you have to do an apprenticeship after secondary school and that the second educational path is out of the question anyway.

Magdalena Polloczek sees the first challenges in career guidance at schools precisely here. She is a research officer for research transfer at the Institute of Economic and Social Sciences (WSI) at the Hans Böckler foundation. The foundation is the study support organization of the German Trade Union Confederation. In addition to doctoral candidates and high-achieving students, it also supports talented young people whose families are unable to finance their studies, for example in the form of scholarships.

Polloczek explains that work placements are more common at secondary school and basic school (Hauptschule), whereas career guidance and preparation at grammar schools are barely developed, which is problematic as all pupils should be equally prepared for their future career aspirations, regardless of the type of school. "Every type of school should support pupils in deciding which training or course of study they can use to fulfill their career aspirations", demands Polloczek.

Struggles and obstacles

During my time at secondary school, I expressed the idea of pursuing a degree rather than an apprenticeship after receiving my certificate, but was then put off by phrases such as "that's far too difficult for you" or "you'll drown at grammar school". Despite my self-doubt and the lack of encouragement from school, I decided, with the support of my parents, to take the higher school certificate and ultimately study at a university. Unfortunately, these self-doubts don't end when you start your studies, and can even be intensified during them. It is not uncommon for working-class children to ask themselves, "Is this the right place for me?", or, "I'm not good enough, I don't deserve to be here". This phenomenon is known as "imposter syndrome". The term was first used in 1978 by psychologists Pauline Clances and Suzanne Imes.

According to psychologists, imposter syndrome is a psychological pattern in which individuals doubt their accomplishments and have a persistent fear of being exposed as a "fraud". People with imposter syndrome often feel like they don't deserve their success, despite evidence to the contrary. This can lead to feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, and self-doubt. It is common among high-achieving individuals and can have a negative impact on their mental well-being and performance. Although there are currently no reliable studies on how common the phenomenon is in certain social classes, it is very relatable for many first generation students.

Sources: AOK; Süddeutsche Zeitung

This is also the case for Cansu Dogan. She is the first in her family to study. Because an academic environment was also new territory to her, she often felt out of place or that she was doing something wrong during her studies. At the time, she found support and understanding from an Arbeiterkind.de group in Aachen. "I just loved the fact that I could talk to like-minded people about all my questions and doubts without feeling stupid", explained Cansu. Arbeiterkind.de is a non-profit organization that encourages pupils from families without university experience to study. Most of the volunteers in the organization are first-generation students themselves, who talk about their own experiences and act as role models. Cansu herself now works as the state coordinator for Arbeiterkind.de in Baden-Württemberg.

"I just loved the fact that I could talk to like-minded people about all my questions and doubts without feeling stupid."

The existence of such organizations shows that there are still many hurdles in the academic careers of first generation students that can be hardly overcome alone without such offers of help.

Deine Meinung interessiert uns

yes

No

This article is part of the group dossier "Educational inequalities in Germany". In this article, our editor Tiana portrays the success story of a working-class child. Lola's article deals with possible solutions that could change the situation.